Fab Trade-Offs: Higher Cycle Time for Higher Yield

Choices fabs make that drive cycle times higher in the interest of improving yield

By Jennifer Robinson

A goal in most wafer fabs is low, predictable cycle time. While there are some structural conditions in fabs that make achieving this goal difficult (high product mix, reentrant flow, time constraints), there are also choices that fab teams make that drive up cycle times. It’s been my experience that fabs regularly trade better cycle time for three things: lower costs/higher revenue, higher yields, and what we’ll call the status quo (resistance to change).

In this article, we’ll discuss the second of these: choices fabs make that drive cycle times higher in the interest of improving yields. We covered choices regarding cost and cycle time in the previous issue and will cover choices regarding the status quo in the next issue. I’m sure those of you who have worked in wafer fabs for many years will have suggestions to supplement this discussion. Please reach out to me via our contact form or on LinkedIn with your suggestions.

First, some remarks on the relationship between cycle time and yield

It’s straightforward to quantify the impact of higher yield on a company’s bottom line. Quantifying the impact of higher cycle time is a much more complex proposition. (See Why and How Fabs Should Focus on CT Improvement (Issue 26.01) for a discussion of financial benefits from cycle time improvement.) What this means in practice is that where they conflict, it’s more difficult to come down in favor of cycle time improvement than it is to come down in favor of yield improvement. This can be true even if a policy has a minimal impact on yield and a substantial impact on cycle time.

The other thing to keep in mind is that yield and cycle time are themselves related, such that improving one is likely (but not guaranteed) to improve the other. We wrote about this back in Issues 5.01 and 5.02 of the newsletter (21 years ago!). After we published our initial thoughts on the relationship between cycle time and yield (mainly that the less time wafers spend in the fab, the less opportunity there is for something to go wrong), we received a wonderful influx of subscriber feedback that helped us to revise our conclusions. You can find both issues in the FabTime Newsletter Archive. They are well worth a look, especially the Subscriber Discussion section in Issue 5.02, where nine people shared their considerable experience with the newsletter community. An updated version of the conclusions that we shared at the end of Issue 5.02 follows.

The relationship between cycle time and yield is complex and involves management trade-offs related to equipment utilization and amount of in-line testing. There may or may not be a relationship between the cycle time and yield of individual lots. Even if there is, it will tend to be difficult to quantify, because of the variability in the fab and the length of the average cycle time. Even if there isn’t a direct relationship for individual lots, we, and many of the people we’ve talked with, believe that some relationship does exist. We think that improving cycle time will tend to improve yields, and vice versa. Some trends related to cycle time and yield are listed below.

- Shorter cycle time leads to increased cycles of learning, and faster yield ramp.

- Shorter cycle time may result in less opportunity for contamination, and hence higher die-per-wafer yields.

- Shorter cycle times can lead to quicker identification of yield problems, through shorter "mean time to detect" errors, and shorter in-line feedback loops.

- Better yield performance can lead to shorter cycle time through a reduction in holds and rework. That is, lots that spend considerable time on hold will tend to have longer cycle times (because of the hold time) and worse yields (because the holds are often because of yield problems to begin with) than other lots.

- Some of the techniques used to improve yield can make cycle time worse. We review four of these in the next section.

Four things that fabs do to improve yield that can also increase cycle time

Of course, not all fabs do all these things. But I’m sure that at least a few of these are familiar to many of you.

1. Let process restrictions lead to single-path operations: A conservative approach for minimizing scrap can be to restrict processing for a given recipe to a single tool, rather than qualifying a second or third tool. Of course, this only applies to situations where the fab has multiple tools in a given tool group.

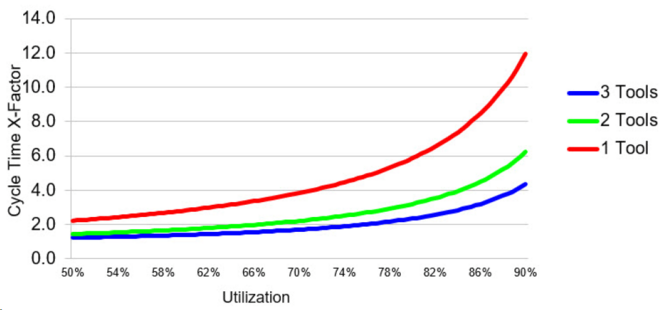

- Likely outcome: Average cycle time per visit through the operation in question will be approximately double what it would be if there were two qualified tools. The reason is that when you only have one qualified tool for an operation, lots passing through the operation are subject to all the variability that occurs at that tool. If the tool goes down, all the lots wait. If there’s a lot with a lengthy process time or a hot lot that jumps to the front of the queue, all the other lots are delayed. When you have two qualified tools, the probability of both of those tools being impacted at the same time by adverse events like these is significantly lower.

- This is illustrated in the graph below, which shows the operating curve for tool groups with one, two, or three tools. At the same utilization per tool, the x-factor on the red curve (one tool) is approximately twice the x-factor on the green curve (two tools). See The Impact of One-of-a-Kind Tools on Fab Cycle Time for more details.

- What you can do: Many fabs have policies that require at least two qualified tools per operation before a new flow is released to production. We’ve even heard of foundries that require three qualified tools per operation. In other cases, a fab will accept single-path restrictions for new low-volume flows, with the intent of qualifying a second tool later, as volume rises. The trick here, of course, is to be disciplined about going back to qualify that second tool. Qualifications can also expire, resulting in a cost in time and labor to re-qualify tools. The obvious risk here is of letting the second (or even the first and only) qualification expire and not re-qualifying tools for the operation.

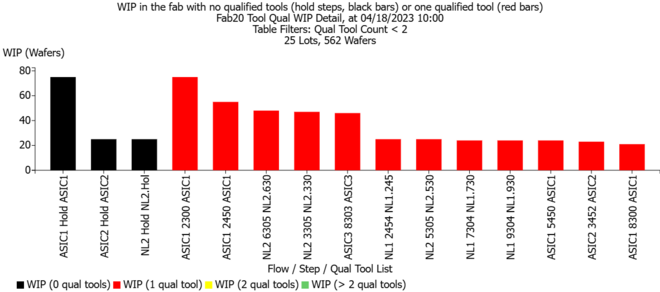

- We recommend regularly reviewing a chart that shows the number of qualified tools for each operation, as shown below. In this example, only operations with WIP waiting are shown. However, a filter can be applied to include other operations that have WIP anywhere along their flow, even if there is no WIP at the operation right now. The point is to have systems in place that check for single-path operations due to process restrictions and encourage process engineers to qualify a second tool.

- INFICON is also working with one of our customers on a new qualification management product that uses optimization to help fabs intelligently manage which tools are qualified for which product and when, based on inventory forecasts. This aligns with our recommendation from the prior issue for fabs to invest to move up the Smart Manufacturing pyramid. Contact us for more information about the new qualification management product.

2. Do too many inspections: If we inspect lots frequently, then we’ll identify problems earlier, improving overall line yield. However, time spent doing inspections is non-value-added in terms of cycle time and also requires operator resources. Inspection tools can become constraints in some cases. It seems obvious that a point of diminishing returns exists, where additional inspections are of limited benefit in reducing scrap, but add significant cycle time.

- Likely outcome: When inspection steps count as moves, teams can be incentivized to over-inspect. Fabs vary in their treatment of inspection steps as moves (or completes, in FPS terminology), and in whether inspection steps “count” as part of manufacturing cycle time. They are non-value-added, in that nothing is added to the wafer, but are still under the control of the manufacturing organization (hence can be considered part of manufacturing cycle time). A lot with a higher percentage of requires inspection will generally have a longer cycle time than other lots.

- A fab that is operator constrained that over-inspects may find that operators are spending time doing inspections rather than making value-added moves. This will negatively impact throughput and profitability for the fab.

- Automated Optical Inspection (AOI), as mentioned in the subscriber discussion forum of this issue, raises the stakes. On the upside, AOI tools can catch defects early, creating a continuous improvement environment. AOI is non-destructive and supports advanced nodes. On the other hand, AOI tools are expensive and take up cleanroom space. High-resolution scans can significantly increase cycle time. AOI tools require significant engineering overhead to make sure that the settings aren’t overly sensitive (leading to false alarms). The subscriber who wrote in above captured the situation well: “Even though AOI process times are not long, we see long queue times for our AOI steps. When we use more AOI, we may improve yield, but we hurt cycle time.”

- What you can do: Fabs can disincentivize over-inspection by not counting inspection steps as moves. They can also measure cycle time contributed by inspection steps (including AOI steps) and analyze the historical relationship between inspection and yield rates, looking for inflection points where yield improvement levels off. Automated software products such as INFICON’s Metrology Sampling Optimizer (MSO) can help here by balancing quality with risk. The system can find the least number of lots to sample to meet the combined requests of engineers. MSO has demonstrated a 30% reduction in lots at risk.

3. Make time constraints between process steps too tight, or too frequent: It’s common in wafer fabs to have time constraints between process steps. A lot must start processing at a later operation within some time window after completing processing at an earlier operation. A common example is a bake step that must be completed within some time window of the prior clean operation. Such constraints are also called queue time limits, time bound sequences, and time links. They are typically put in place by process engineers to improve yields in the fab. When the time windows are too tight relative to operational conditions in the fab, cycle time and capacity can be wasted, particularly if there are multiple steps inside the time constraint loop. When there are many time constraints in the fab, scheduling and dispatching are more challenging (though of course advanced scheduling software like the INFICON Factory Scheduler can help).

- Likely outcome: When a time constraint is violated, the lot must go back to the first operation in the sequence for reprocessing. When this happens, capacity is lost at tools running the first operation (increasing cycle time for all lots that use that tool), and cycle time of the reprocessed lot is increased by the reprocessing time. There is also increased variability in the arrival rate to the later operation. There can be intervening steps between the initial and final operation of a time constraint loop. These multi-step systems are particularly difficult to manage. Even a system involving two steps holds considerable complexity.

- Another outcome that can happen in the presence of time constraints is that operations teams are so determined not to violate them that they hold WIP outside of the time constraint loop until the downstream tool is available. Unless carefully managed, this can inflate queue time at the upstream tool and waste capacity on the downstream tool.

- What you can do: Time constraints between process steps are a hidden source of cycle time that is directly driven by yield improvement goals. The thing to do then, to better manage this trade-off, is make the cost in terms of cycle time more visible. Exactly how you do this will depend on your fab MES and how you log transactions. One idea is to add a rework code that includes “violated time constraint,” so that you can filter for move transactions matching that code. Then you’ll know how frequently lots are reprocessed at a given tool or operation.

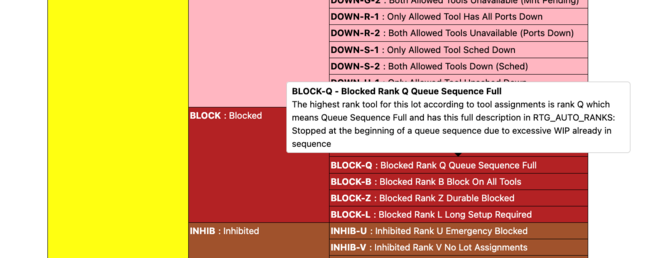

- A clue to the more subtle issue of people holding lots upstream waiting for the downstream tool to be available is significant Standby-WIP-Waiting time on the first tool in the time constraint loop. Logging the tool to a sub-state like “waiting for time constraint loop to clear” would allow filtering to view this data. Alternatively, you could have a WIP state like “waiting to enter time constraint loop” as a subset of queue time. In INFICON’s Enhanced Cycle Time (ECT) state model, we have a state called Block-Q, or Blocked Rank Q Sequence Full, that captures the fact that the lot is “Stopped at the beginning of a queue sequence due to excessive WIP already in sequence.” This state will be displayed in future versions of FabTime and can be used to make the cost of such time constraints more visible.

- You can find recommendations for minimizing time constraint expiration in this article: Managing Time Constraints between Process Steps in Wafer Fabs (Issue 24.02).

4. Tie future holds to a specific engineer, turning process engineers into effective one-of-a-kind tools: Every fab that I know of uses future holds. Future holds are situations where an engineer specifies that a lot will go on hold at some future step, so that the engineer can check something. Future holds can help with yield because the engineer identifies ahead of time where there might be a problem and plans an appropriate intervention. The problem with future holds, however, is that they are frequently tied to a specific engineer. That engineer might be unavailable at the time that the future hold comes due.

- Likely outcome: Future holds generally inflate the cycle time of the lot in question. Most fabs run 168 hours a week, 50-52 weeks a year. That’s 8400 to 8736 hours a year (not counting leap day). Process engineers are people. They go home at night. They take vacations. Sometimes they’re out sick. They’re on-site for something like 25% of the time that the fab is running (even if it feels like more than that!). And even when they’re there, they are usually busy with other things. What this means is that when you have a future hold for a specific engineer, there is an excellent chance that when the future hold comes due, that engineer will not be available. This leads to increased cycle time.

- What you can do: The obvious thing to do here, just like with the single-path operations, is to make a backup available. Every future hold should have a primary and a secondary engineer (who ideally don't work on the same shift). Alternatively, some sort of team structure should be set up, like a call schedule for doctors, where someone is responsible for triaging the future holds when they come due. What makes sense for a given fab will depend on that fab’s situation. (How many engineers are there? How frequent are the future holds?) The important thing is not to create situations where your process engineers act like one-of-a-kind tools.

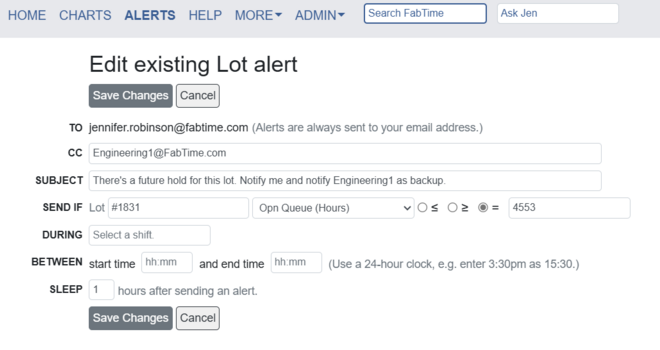

- In our FabTime reporting software, engineers can set up automated alerts for future holds. (“Notify me when Lot XZY reaches Step ABC.”) When triggered, the alert automatically goes to the email address of the person who created the alert. However, that person can also send the alert to another email address, which could be a team address. We highly recommend this practice. An example is shown below.

Conclusions

The interaction between cost and cycle time, as outlined in the first article of this series, is predictable (non-linear, but predictable). You can spend money (on tools, staff, or software tools) to reduce cycle time. Being more frugal about such spending is likely to increase cycle time. With cycle time and yield, the relationship is more complex. While reducing cycle time will tend to improve yield (through faster identification of defects and shorter learning cycles), the impact of yield improvement efforts on cycle time is more mixed.

More restrictive tool qualification tends to reduce scrap. But we know that cycle time is much higher through single-path operations. More frequent inspections allow quicker problem detection and improve yields. Again, this is at a cost of higher cycle time. As fabs advance to Automated Optical Inspection (AOI) the problem is magnified, because the inspection tools are more expensive and more likely to be run at a high loading that drives up queue time. Time constraints between process steps and future holds are other examples of techniques used by engineers to maximize yield that can be counterproductive for cycle time.

None of this is to say that fabs shouldn’t use these yield improvement techniques, of course. But it’s worth considering the trade-off in increased cycle time, particularly given that shorter cycle times in and of themselves can help to improve yields.

Closing Questions for Subscribers

Does your fab do any of the things mentioned above? What else would you add to this list? (Any responses shared will be shared anonymously.)

Further Resources

All past FabTime newsletters are available in PDF format from the FabTime Newsletter Archive. Please reach out to me for the link or look in the most recent email issue of the newsletter. You can download individual issues or download a zip file containing all past issues. Some articles have been re-published on the INFICON website. Those are linked above where mentioned.

Further reading from this issue: